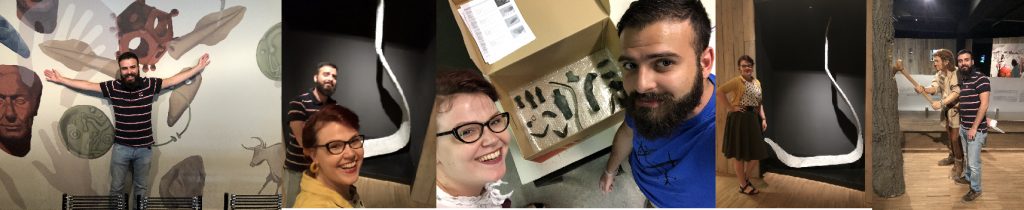

Last week I once again traveled abroad with Valerio Gentile to examine finds from an exceptional prehistoric grave. This time we went to Tongeren, which (apparently) is the oldest town in Belgium, and once was the only Roman administrative capital within the country’s borders (thanks Wikipedia). We stayed at a lovely interbellum house situated at the beguinage (begijnhof, in Dutch), which we highly recommend should you ever need a place to stay in Tongeren.

While being surrounded by Medieval city walls and the beguinage certainly added to the experience, we, of course, came to see some prehistoric finds! This time it was the Gallo-Roman museum that hosted us. There we were kindly granted access to a selection of artifacts that I have wanted to examine for YEARS, but have never had the chance to (as they were either part of a touring exhibition or mounted in the exhibition in such a way that they could not be removed). But the archeology gods finally smiled on me, and everything came together at the right time – so south we went. In Tongeren, we examined the exceptional bronzes found in Neerharen-Rekem tombe 72. This grave was found in an urnfield in the 1970s and yielded cremation remains, as well as three bronze Gündlingen type swords, three bronze spearheads, two chapes (parts of a scabbard), a bronze ring and an intriguing small plate of iron.

As we also did in Frankfurt, Valerio conducted a microscopic use-wear analysis of the weaponry, while I turned my attention to trying to reconstruct how the objects were made and looked for signs of how they were used and treated during the burial ritual. The bronzes proved to be an intriguing puzzle. We already knew that they had been bent, broken and burned as part of the funerary ritual, but it proved challenging to determine exactly how this was done. Had they been broken and then burned, or burned and then broken? Was the burning the result of being on the pyre? Answering all these questions will help us reconstruct exactly how the Neerharen-Rekem funerary ritual was conducted, which in turn can help us understand the role of this burial in the development of the elite funerary rite in the Low Countries.

For the finds we examined not only form a personal holy grail, but they also form a key site in many archeological debates. During most of the Late Bronze Age, weaponry was deposited in primarily wet places as part of some kind of ritual and never placed in burials. At the very end of this period, for some as yet unknown reason, social customs started to change and weaponry started being deposited as grave goods as well as in other locations. For a time, both social practices existed side by side, and the Gündlingen type swords are actually the first to be found both in burials and ritual depositions.

The Neerharen-Rekem burial has been 14C-dated to the 9th century BC, which makes it both a Late Bronze Age grave as well as one of the earliest elite burials of the Low Countries. As such this burial could help us understand how the elite burial practice developed. It once again proved very helpful to analyze this material together with Valerio and be able to discuss impressions, observations and ideas, something that I previously never was able to. We ended up with a hypothesis for the series of events that resulted in these bent, broken and burned bronze, but we will need to do some destruction experiments to confirm our suspicions!

The staff members of the Gallo-Roman museum made us very welcome and were a delight to work with. They even invited us back this fall to examine material from other sites! They furthermore indicated their willingness to make the cremation remains from the Neerharen-Rekem burial available for examination, which is particularly exciting. While such an analysis was done in the 1970s when the grave was discovered, results from any such examination done prior to the 1990s need to be taken with a grain of salt. Cremation analysis at the time was a relatively new technique, and experience has taught us that analyses done using new, and better techniques can sometimes yield different (and more accurate) results. Even so, the 1970s analysis did yield some very interesting results (which is why we want to have them confirmed with new techniques) – it identified three adults in this grave: two males and one female. If the older analysis proves correct, then the presence of three swords and three adults would seem to suggest they once belonged to the decedents, which means we are perhaps dealing with at least one female warrior here. Being a woman myself I, of course, love this idea, but actually age and sex determinations for the elite burials are always exciting, as so few cremation remains have survived. Many of the Dutch and Belgian elite burials were found by chance or excavated long ago, and cremation remains generally did not survive either process. As a result, we rarely know anything about the people buried in these burials, so we are fortunate that the Museum has indicated its willingness to make the remains available for a new analysis, which we hope to have done in the near future.

Once again I am afraid I cannot share too much more of our discoveries as we are still working through our analyses, but I still wanted to share something on the exciting material that we got to analyze as well as our experiences in Tongeren. Should you ever get the chance, I highly recommend you visit this museum as it is one of the most lovely ones I’ve ever been to. Oh, and did I mention they have wall paintings of one of the spearheads we examined and a HUGE replica of one of the bronze swords we studied? 😀

0 Comments