Anyone who has ever heard me talk about my research into Early Iron Age elite burial practices, has heard me refer to the Hallstatt Culture of Central Europe. In this blog post, I give a short introduction to this exceptional site and provide some links to other websites and (accessible) books that you can check out if the following peaks your interest. And should you ever have the opportunity, I highly recommend a visit as it is truly one of the most beautiful and interesting places I have ever been to.

The Hallstatt Culture is named after the village of Hallstatt in the district of Gmunden in Upper Austria. This old mining town is part of the Dachstein / Salzkammergut Cultural Landscape, one of the World Heritage Sites in Austria. Situated on the southwestern shore of the Hallstätter See, it is literally built on the steep slopes of the Dachstein massif, which combined with the local architecture style lends this striking town its unique appearance.

The abundant salt deposits that lie just a few meters under the surface in this region have kept people coming to this area for over 7000 years. Not only does the human body require salt to function, prior to modern times, but salting was also one of the most reliable ways of preserving food. Curing with salt not only makes it possible to store food for longer periods of time, but it also makes food transportable over long distances. Salt was indispensable, and as it was not available everywhere in the past, it was also a precious commodity.

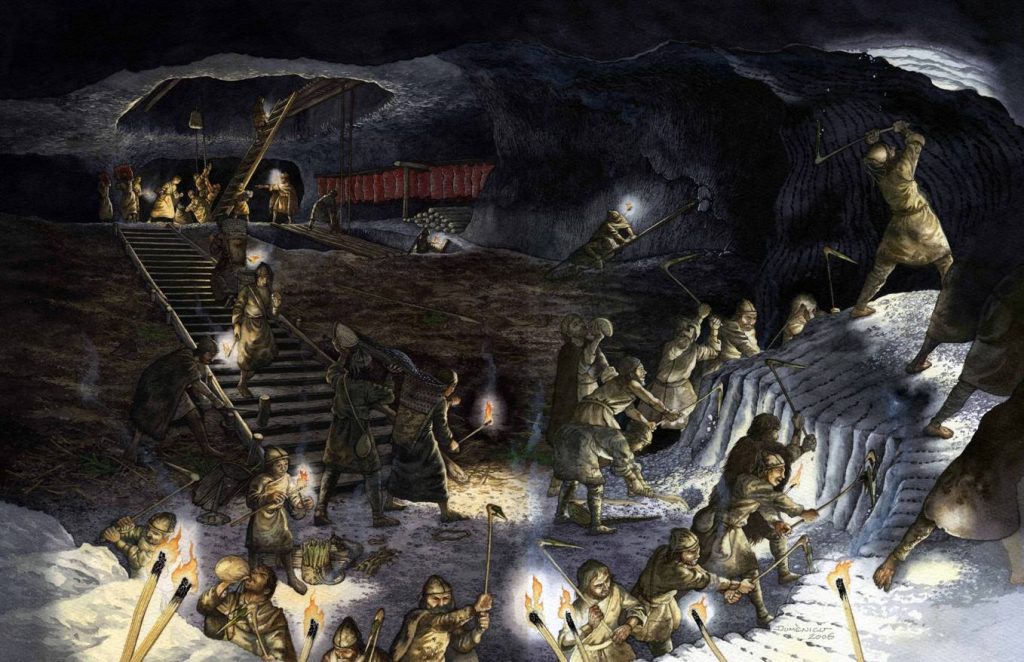

While there is some evidence of salt exploitation at Hallstatt from the Neolithic onwards, systematic mining of the white gold really took off during the Bronze Age, with a massive resurgence in a big way during the Early Iron Age. The salt, so valued for its preservative properties, also resulted in the excellent preservation of organic material left in the shafts by the miners – including tools, bags, shoes, scraps of clothing, dyed textiles, torches, food remains, feces and even complete wooden structures, such as the famous Bronze Age staircase.

There is even a word for the compact mixture of the waste created during prehistoric mining activities in which these finds are found: ‘Heidengebirge’. We know from these finds that the miners were extremely efficient, and can even reconstruct the toolkit and techniques they likely used. As one of two major salt production centers in the eastern Alpine region, Hallstatt soon established itself as a place of importance. And its inhabitants soon grew wealthy, with one of the results likely being the rich grave goods buried with the dead in the Early Iron Age cemetery.

The Hallstatt cemetery

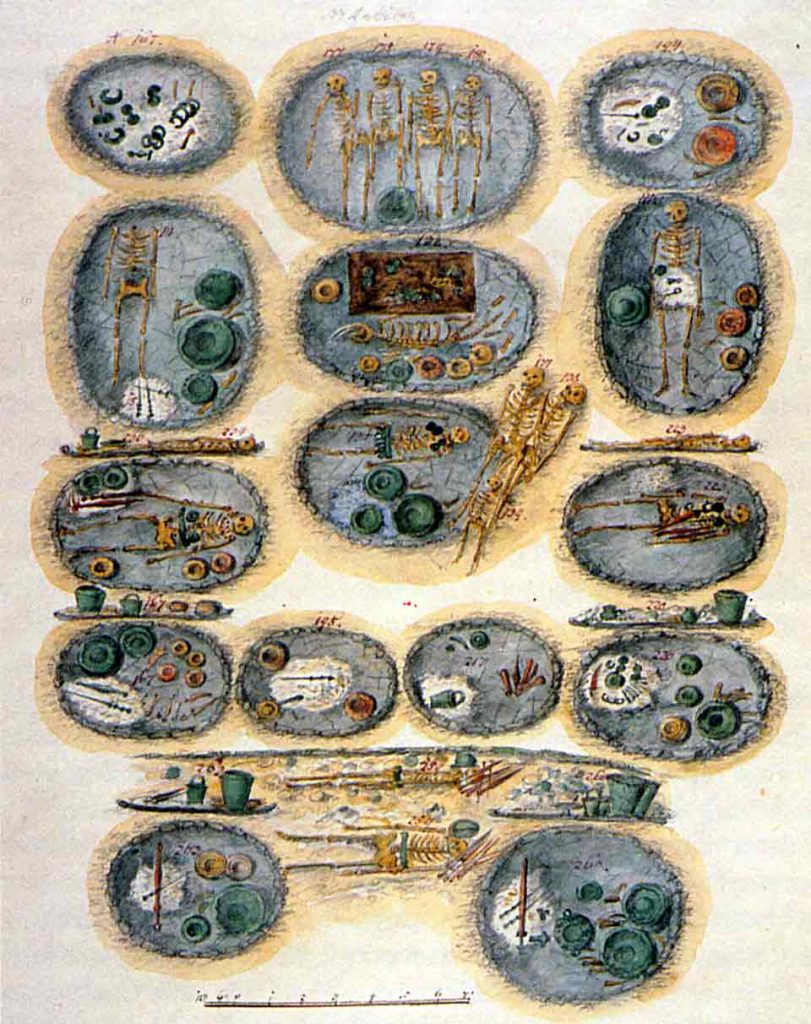

The Early Iron Age cemetery of Hallstatt is world-famous and together with the prehistoric salt mines contribute to Hallstatt’s status as one of the world’s most outstanding archeological sites. Already from the 1600s onwards, there are records of occasional prehistoric finds being encountered during mining activities at Hallstatt, but it wasn’t until the second half of the 19th century AD that Bergmeister (how cool is that for a title?!) Johann Georg Ramsauer conducted systematic excavations of the Early Iron Age cemetery at Hallstatt. His work is well known not only because of the exceptional finds he did here, but also the beautiful watercolors through which he recorded his work. The detailed documentation is exceptional for the era in which he worked – a time when archaeology did not yet exist as a profession, and we are lucky to know as much as we do about this cemetery. In the almost two decades that he excavated here, he uncovered over a thousand graves. In the years since, burials continued to be uncovered and excavated, even in recent years. Today the tally stands at approximately 1500 burials!

Two different customs were practiced here, apparently side by side: inhumation (whereby the body is buried intact), and cremation (whereby the deceased is burned and their remains interred). The Hallstatt graves are characterized by comparatively rich grave goods, with generally speaking the cremation graves appearing ‘richer’. The finds done are quite simply dazzling. They include weaponry such as swords and daggers, as well as sometimes defensive armor such as helmets. Unbelievably stunning ornament sets and jewelry have been found here as well, frequently made of bronze, but also of bone, amber, and even gold. The latter two materials were precious and often luxurious imports. Frequently not only the precious material but also the source of an object seems to have added to its value, as it appears that a high proportion of the objects found at Hallstatt were made elsewhere, sometimes from very far away.

While organic grave goods such as food or drink generally don’t survive in these graves, it is highly likely that such items were included in many of the funerary assemblages. This is indicated, for example, by the vast array of bronze vessels – predominantly food and drink vessels – which have been found. Overall the grave goods from this cemetery suggest a life well above subsistence level, and it is believed that their connection with the mine and the precious salt they traded in contributed to this.

Today you can visit both the town of Hallstatt and enjoy not only its unique architecture and atmosphere, but you can also see some of the archeological finds done here in the local museum (more are on display in Vienna).I spent half a day there geeking out, it’s AMAZING! Also amazing are the salt mines themselves which you can tour and learn about how salt was mined through the millennia, and even see traces of prehistoric activities. For more on visiting Hallstatt, please see their website here. If you want to learn more about this town and its fantastic history and the archaeological finds from home, please check out, for example, the Natural History Museum’s website, or for example these very accessible books: Kingdom of Salt: 7000 years of Hallstatt or Hallstatt 7000.

0 Comments