Early Iron Age (800–500 BC) elite burials in the Low Countries

My fascination with Early Iron Age elite burials started during my Research Master when I was interning at the National Museum of Antiquities. For a year I assisted the curator of the Prehistory collection Luc Amkreutz to redo the permanent exhibition of the archaeology of the Netherlands. As part of this process, I helped arrange the finds from the Chieftain’s burial of Oss into its new display case. This iconic find from Dutch prehistory has fascinated many since its discovery some 80 years ago, and I am the fourth ‘generation’ to study this burial complex – and I doubt that I will be the last.

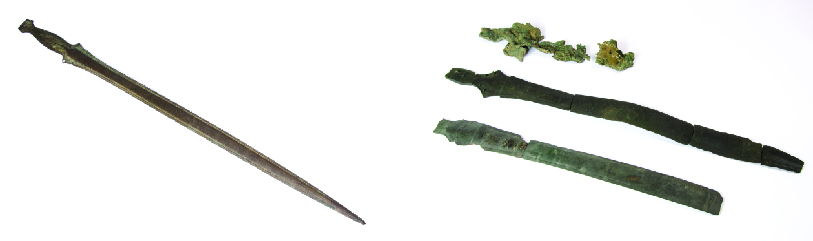

This Chieftain’s burial consisted of a large bronze wine-mixing bucket (known as a situla) which was used as an urn for the cremated remains of the dead Chieftain and his belongings. These included an extraordinary iron Mindelheim type sword with a gold-inlaid hilt which had been bent round during the funerary ritual, horse-gear for two horses, parts of yoke (which would have been used to attach the horses to a wagon), an iron ax and knife, three dress pins, a ribbed wooden bowl, some worked bone and antler fragments and lots of textiles.

I found myself completely fascinated by these items, both the exceptional craftsmanship of them, but also the puzzles they represent – on several levels. Firstly, there was the challenge of figuring out exactly what all the bronze and iron bits were and how they would have gone together. I knew many of them were horse-gear and wagon components, but how would they have been positioned on the organic components that did not survive (see also this post on reconstructing Early Iron Age elites and their burials and wagons)? Then there was the question of how and why it all ended up in the bronze situla. Why did the mourners take apart a wooden yoke and bend the sword during the funerary ritual? Why did this man warrant such an elaborate funeral? And then perhaps the most interesting (to me that is) element to this complex – most of the grave goods originated from the Hallstatt Culture of southern Central Europe, with nothing similar found in between. Moreover, the Chieftain’s burial of Oss is not the only such grave to be found in the Low Countries.

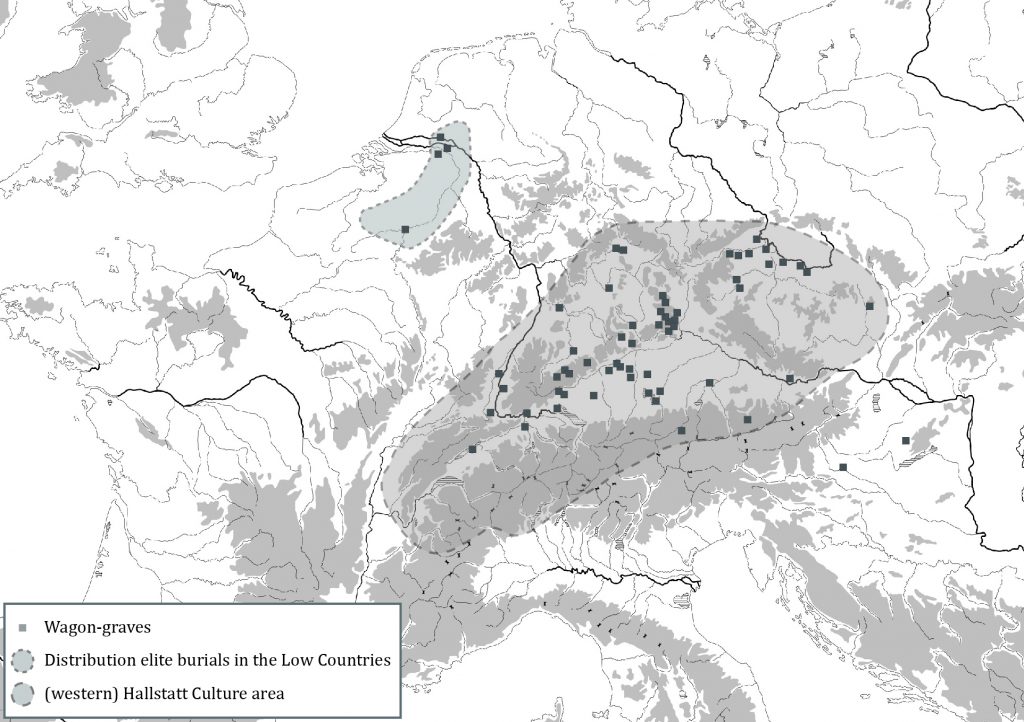

There is, in fact, a cluster of Early Iron Age (800–500 BC) elite burials in the Low Countries in which bronze vessels, weaponry, horse-gear and wagons were interred as grave goods. Mostly imports from Central Europe, these objects are found brought together in varying configurations in cremation burials generally known as chieftains’ graves or princely burials. In terms of grave goods, they resemble the Fürstengräber of the Hallstatt Culture of Central Europe, with famous Dutch and Belgian examples being the Chieftain’s grave of Oss, the wagon-grave of Wijchen and the elite cemetery of Court-St-Etienne. These burials formed the focus of my PhD-research, an in-depth and practice-based archeological analysis of the Dutch and Belgian elite graves and the burial practice through which they were created. The results of this project are published by Sidestone Press in Fragmenting the Chieftain as part of the PALMA series of the National Museum of Antiquities.

Studying the Dutch and Belgian elite burial was not without its challenges. The quality of the available data generally is quite low as most graves were unearthed several decades to several centuries ago and context information generally is limited. In my PhD I strove to overcome this by going back to the original data, performing thick descriptions on surviving finds and studying even the most unprepossessing fragments. This revealed how much still can be learned from a comprehensive and detailed re-examination of all available documentation and artifacts from elite burials. While it is true that context information for many is extremely poor, limiting interpretation, detailed study of what remains and comparison with newer and better-excavated finds allows for the reconstruction of the elite funerary practice in surprising detail. All information regarding the individual graves gathered from literature study and object examinations was compiled in an accompanying Catalogue Fragmenting the Chieftain – Catalogue. Late Bronze and Early Iron Age elite burials in the Low Countries, which for many of these graves is the first English and accessible publication. This inventory forms the dataset used to analyze the elite burial practice. Iconographic overviews of grave contents and the treatment of objects are used to visualize the burials analyzed, which allows for the recognition of patterns in terms of grave goods composition and treatments.

The elite burial practice arises following a shift from depositing certain supra-regional objects like swords and ornaments to interring them in graves during the Late Bronze–Early Iron Age transition. These changes are argued to reflect changes in attitude towards (markers of) supra-regional (elite/warrior) identities. For a short time, certain exceptional objects could end their lives in depositions as well as in graves, and it appears that eventually burial deposition became preferred. The practice of interring individuals with bronze swords arose in the 9th century BC, and those with Hallstatt Culture imports occurring also early in the 8th century BC and continuing into the 7th century BC. This was established using new (calibrations of) 14C-dates and typochronologies, which revealed that the majority of burials either are or could be earlier than generally thought. When combined with the origins of certain grave goods and the cultural context they reflect, this adjusted chronology revealed that Atlantically-oriented bronze sword-graves are actually closer together with the Hallstatt Culture-oriented ones (in terms of the origin of the objects they contain). Where before these were perceived as chronologically separated phenomena, they in fact overlapped and apparently smoothly transitioned from one into the other. Significantly, the practice of identifying deceased as elites through lavish grave goods started before there is any material evidence of contact with the Hallstatt Culture of Central Europe. This means that the rise of the elite burial practice was, in fact, a local development (as has been argued in the past as well by Fontijn and Fokkens in 2007).

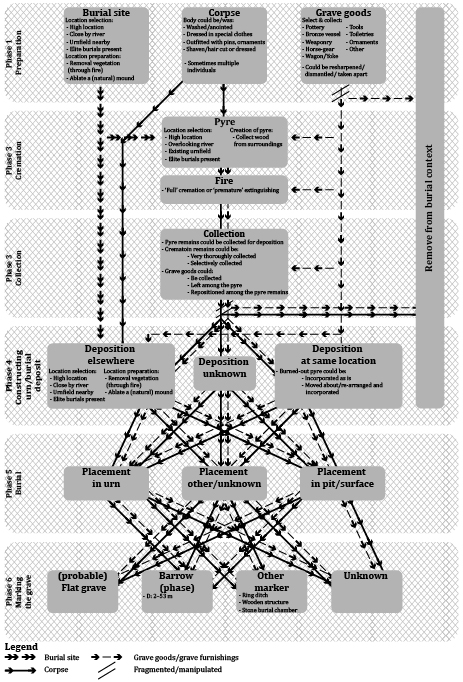

The burial practices reflected in the elite burials are visualized in chaîne opératoire-style infographics, which reveal that in most cases, the burial practice through which the dead were interred was decidedly local in nature and, with the exception the grave goods interred, apparently ‘unremarkable’. People were buried in the ‘usual (urnfield) fashion in the usual places’, primarily in high and striking locations in the landscape and generally in or by urnfields and/or barrow groups. Sometimes there is a single elite burial per site, but generally, there are more. Sometimes the elite burials represent a short burst of activity, sometimes they reflect a longer period of time. The elites were laid to rest through rituals involving the cremation of the dead and the dismantling, burning, bending and breaking of grave goods, and pars pro toto depositions of both. In terms of how they were buried, owning (only) a bronze vessel, a sword or horse-gear does not appear to have warranted exceptional treatment during the burial ritual.

Analysis of the burial practice reveals that in fact with regard to how individuals were interred, it were those accompanied by wagons and wagon-related horse-gear that were laid to rest through an exceptional, exaggerated burial practice that strongly incorporated the dismantling, manipulation and fragmentation of grave goods. Pars pro toto depositions of both human remains and grave goods are emphasized in these graves and they regularly feature the use of textile as part of the burial rituals which appear grander in nature and execution. Recognizing this common denominator, the wagon, is not always easy due to the destructive and selective nature of the burial practice.

In an attempt to understand this difference in funerary treatment, that appears linked to the type of grave goods that accompanied the dead, I explored how the (kinds of) objects found in the elite burials were treated in life. Focusing in particular in a very practical sense on how they were used, but also considering how they were perceived and what they may have symbolized. By doing so it was established that the (types) of objects found as grave goods in the elite burials played a role in the construction and expression of a complex identity. The bronze vessels, weaponry, horse-gear and wagons, as well as the tools and ornaments both were symbolically charged items and very much a part of daily life. It were the exceptional wagons and accompanying horse-gear, however, which reflect truly new social practices in the Low Countries, and it was likely this in combination with the religious significance that they held (cf. Pare 1992, Ch. 12), that triggered their, and their owners’, exceptional treatment in death.

In conclusion, it was established that the elite burials are embedded in the local burial practices – as reflected by the use of the cremation rite, the bending and breaking of grave goods, and the pars pro toto deposition of human remains and objects, all in accordance with the dominant local urnfield burial practice. It appears that those individuals interred with wagons and related items warranted a more elaborate funerary rite, most likely because these ceremonial and cosmologically charged vehicles marked their owners out at exceptional individuals. Furthermore, in a few graves the configuration of the grave goods set, the use of textiles to wrap grave goods and the dead and the reuse of burial mounds show the influence of individuals familiar with Hallstatt Culture burial customs.

For more on these exceptional burials, please see the two volumes of my dissertation Fragmenting the Chieftain, which can be read or downloaded here, and ordered from Sidestone Press here.

References

Fontijn, D. & H. Fokkens, 2007. The emergence of Early Iron Age ‘chieftains’ graves’ in the southern Netherlands: reconsidering transformations in burial and depositional practices. In: Haselgrove, C. & R. Pope (eds), The Earlier Iron Age in Britain and the Near Continent, Oxford: Oxbow, 354–373.

Pare, C.F.E., 1992. Wagons and Wagon-Graves of the Early Iron Age in Central Europe (Oxford University Committee for Archaeology Monograph 35), Oxford: Oxford University Committee for Archaeology.

0 Comments